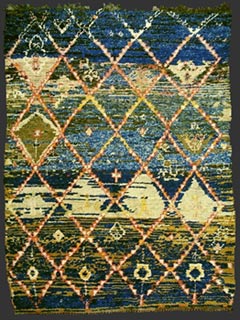

Antique Berber and Moroccan Carpets

Antique Berber and Moroccan CarpetsAntique Berber and Moroccan carpets and textiles have become increasingly rare over the past twenty

years.

Those that remain and are still available to the collector are now being offered online to galleries, interiors designers, private collectors and traders by Yallah Morocco as a selection of the finest traditional pieces. There is a limited supply of these carpets and they are in excellent and authenticated condition

Tribal customs, though disappearing, are kept alive and are still reflected in the brilliant and innovative traditional arts of dyeing and weaving in rural Morocco.

Morocco's rural weaving culture has attracted a great deal of attention from the international art world over the past 20 years. Much of this interest has been generated by a new generation of dealers and collectors who have used their understanding and appreciation of abstract modern art to judge these weavings, thereby gradually replacing the use of fineness, natural dyes and age as indicators of quality.

Morocco's rural weaving culture has attracted a great deal of attention from the international art world over the past 20 years. Much of this interest has been generated by a new generation of dealers and collectors who have used their understanding and appreciation of abstract modern art to judge these weavings, thereby gradually replacing the use of fineness, natural dyes and age as indicators of quality.The minimalist and abstract forms seen in these rural weavings seem to both suggest an affinity with the earliest roots of the pile-weaving as well as represent the contemporary yet authentic creative and archaic spirit of tribal art.

Appreciation of the spontaneous and bold character of Moroccan Berber carpets began in the 1920s and 30s with classical modern architects such as Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto or Marcel Breuer who integrated them into their interiors and promoted them in important presentations and the interiors shops of the period.

Moroccan weavings can be divided into various categories. The sophisticated Arabic urban tradition has been subject to cultural exchange with the Mediterranean and was greatly influenced by the styles of the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century. The carpet production of the nomadic Arab tribes is of minor importance, apart from the products of the Haouz region. In the urban embroideries of the 18th and 19th century the influence of the Moorish and Jewish migrants who moved back to Morocco from Spain in the late Middle Ages are still visible.

On the other hand the rural carpets of Morocco have followed regional Berber cultural traditions and appear to have a style that remained independent until the 20th century. And since there was not really a European demand before the 20th century, Moroccan carpets have always been produced mainly for personal needs or an internal market. It is surprising that the influence between the urban centres and the remote Berber regions was relatively small with the exception of the relation between the urban centres of Rabat and Salé to the Jebel Siroua region and parts of the Ait Ouaouzguite confederation. Otherwise only the Oulad bou Sbaa in the south-western part of the Haouz plains seem to have produced carpets orientated on an urban style before the 20th century.

On the other hand the rural carpets of Morocco have followed regional Berber cultural traditions and appear to have a style that remained independent until the 20th century. And since there was not really a European demand before the 20th century, Moroccan carpets have always been produced mainly for personal needs or an internal market. It is surprising that the influence between the urban centres and the remote Berber regions was relatively small with the exception of the relation between the urban centres of Rabat and Salé to the Jebel Siroua region and parts of the Ait Ouaouzguite confederation. Otherwise only the Oulad bou Sbaa in the south-western part of the Haouz plains seem to have produced carpets orientated on an urban style before the 20th century.URBAN CARPETS

Unlike in classical eastern carpet-producing countries, it is not known whether urban pile-weaving workshops were established before the 18th century, although Charles Grant Ellis and Jenny Housego suggested that a group of Mamluk carpets may have been manufactured in western North Africa (*1). It is safe to assume that the 18th century urban workshops of Rabat were established to adapt Anatolian examples to the specific demand for long and relatively narrow carpets in Moroccan urban houses for those that could not afford the prestigious but expensive imported pile weaves. Descriptions of an urban household in the kingdom of Fez in a French geographical encyclopaedia (*2) from the early 18th century speak about the floors being covered with carpets from wall to wall but neither describe the carpets themselves nor mention their origin.

The few examples of Rabat carpets we know from before or around 1800 appear related by design to Anatolian village rugs from Melas, Ladik, Mucur and the so called “Transylvanian” carpets from western Anatolia, but combined with regional Moroccan motifs (1 +2). These rugs first show the recognisable Moroccan trait of giving more weight to the borders and less to the main field (3). The colour scheme appears balanced in this period and the colour palette is limited compared to the carpets from later than 1850. Rabat and Médiouna have to be regarded as the main centres of Moroccan urban pile weaving, while Salé is known for a special type of textile consisting of a mixture of pile and flat weave (4).

The few examples of Rabat carpets we know from before or around 1800 appear related by design to Anatolian village rugs from Melas, Ladik, Mucur and the so called “Transylvanian” carpets from western Anatolia, but combined with regional Moroccan motifs (1 +2). These rugs first show the recognisable Moroccan trait of giving more weight to the borders and less to the main field (3). The colour scheme appears balanced in this period and the colour palette is limited compared to the carpets from later than 1850. Rabat and Médiouna have to be regarded as the main centres of Moroccan urban pile weaving, while Salé is known for a special type of textile consisting of a mixture of pile and flat weave (4).By the second half of the 19th century the style of Rabat carpets developed towards a “design-overload” and an extremely diverse colour palette.